The value of an option is based on the value of some underlying asset. Call option buyers are obligated to acquire the underlying asset (stock, for example) at the option's specified price on or before the option's expiry date, but they are not obligated to do so at any time before that. In the particular instance of a put option, the bearer of the option agreement has the privilege but not the responsibility to sell the underlying asset. However, could you elaborate on what that suggests? Read on for a closer analysis!

What's a call option?

The purchaser of a call option has the privilege, but not the responsibility, to purchase a stock, asset, commodity, and perhaps other commodity or instrument from the option seller at a certain price and within a predetermined time frame. The core asset is indeed the share, bond, or commodity itself. When the value of the underlying asset rises, the purchaser of the call option benefits. A call option differs from a put option in that the holder has the authority to sell the asset at a stated value on or before expiry.

Learning about Call Options

Consider stock as the underlying asset. Call options provide the bearer the right to acquire 100 shares of a firm at the specified value (exercise price) until the expiry date. For instance, the holder of a single call option contract may be granted the privilege, up until the expiry date four months later, to purchase one hundred shares of Apple stock at a price of one hundred dollars per share. Traders may choose from a wide range of available expiry dates and strike prices. An option contract's cost rises in tandem with an increase in the value of Apple stock and falls when the stock's value falls.

The purchaser of a call option has the option of holding the agreement until its expiry and then either taking delivery of hundred shares of stock or selling the contract at any moment up to the end date at the contract's then-current market price. When you purchase a call option, you must also pay the price (the premium). The cost of purchasing a call option is the consideration for the right to exercise such an option. The premium paid by the call purchaser has forfeited if the underlying asset's value is lower than the strike price at expiry. This is the worst possible outcome.

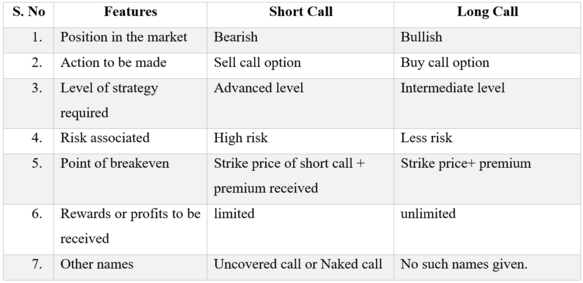

Comparison of Long and Short Call Options

You may buy and sell call options in two fundamental ways.

Long call option:

Simply put, a long call option seems to be a call option in which the purchaser is granted the right but not the responsibility to purchase the underlying stock at the option's specified strike price at some point in the future. If you want to buy shares at a lower price in the future, a long call may let you do so strategically and in advance. In preparation for a potentially noteworthy event, such as a company's earnings call, you may decide to buy a long call option. In contrast to the potential infinity of gain from a long call option, the maximum risk you may incur is the cost of the premium. Thus, even if the firm doesn't announce a favorable profits beat (or one that doesn't meet market forecasts) and also its shares decrease, the purchaser of a call option will only lose the option's premium.

Short call option:

A short call option is indeed the inverse of a long call option, as the name suggests. When an option is short, the seller makes a future commitment to sell the holder stocks at the option's specified price. Short call options are mostly used for "covered calls" by the person selling the option. This signifies that the seller already possesses the stock that the option is based on. If the deal goes against them, the call might assist limit their losses.

Do Call Owners have a Choice to Acquire the Underlying or an Obligation?

The premium represents the prevailing market value of the option. The premium represents the cost of purchasing the call option. A call buyer ends up losing their premium if somehow the underlying asset's price is lower than the strike price when the option expires. They are not obligated to pay more than the stock's current market price in order to make a purchase. If it is higher than the strike price, nevertheless, the buyer might acquire the shares at a significant discount to their current market price.

Consequently, unlike futures &'' forward contracts, options contracts allow the investor the opportunity to actually fulfill the deal. In other words, the buyer of an option is under no compulsion to actually purchase the underlying stock at the strike price. They only possess the legal authority to do so if they so choose. For simplicity's sake, let's assume that an investor pays $1 for a one-week XYZ call option with a $ten strike price and an expiration date in the following week. The investor has the right, but not the obligation, to purchase 100 shares of stock at $10 a share if the stock is trading at $10.25 the day following the call option is purchased.

Derivative obligations

Contracts to purchase or sell a commodity or securities at a future date and price are called futures or forward contracts, and they differ from options in that they are legally binding. If retained at contract expiry, the underlying asset must be delivered if it is short or taken if it is long. When one purchases a futures or forward contract, he or she assumes the responsibility to purchase and take delivery of the underlying asset at the contract's expiration date. The contract's seller is taking on the responsibility of providing and delivering the underlying asset at the end of the contract's term. In order to simplify trading on a futures market, the quality and quantity of futures contracts are standardized. Though forwards provide more flexibility, they are traded bilaterally or "over-the-counter" (OTC).

Conclusion

A person who has a call option contract has the right to purchase the underlying asset at an agreed-upon price. If the value of the underlying asset increases above the strike price prior to the option's expiry, the holder may execute the option, requiring the option's seller to transfer the shares at the higher price. The option buyer is only out of the initial fee paid for the call if the underlying price never rises over the strike before the option expires.